The World Health Organization reports that nearly 1 billion people live with a mental disorder worldwide, with someone dying by suicide every 40 seconds. In the United States, the National Institute of Mental Health estimates that 1 in 5 individuals have a mental illness, while the Mental Health America Report found that 60 million adults (23.08%) experienced a mental illness in the past year, with nearly 13 million adults reporting serious thoughts of suicide. Most alarmingly, nearly half of all youth undergoing screenings for depression reported frequent suicidal thoughts. The CDC’s preliminary 2023 statistics indicated 49,266 suicides among individuals starting as young as age 12 and older, which is about one death every 11 minutes. Additionally, a 2006 study found that people with severe mental illness die 14 to 32 years earlier than the general population.

These numbers reveal a broken mental health system that’s fragmented, outdated, and stigmatizing, hindering people from seeking services. The situation is worsening with massive federal cuts to mental health services, including a 50% reduction in SAMHSA staff and $11.4 billion in COVID-era funding cuts linked to addiction, mental health and other programs. With potential cuts to Medicaid, and millions losing health insurance, access to treatment will face unprecedented challenges. The troubling trend toward re-institutionalization undermines decades of progress, moving away from proven alternatives like peer support services, and setting back the potential for people to recover.

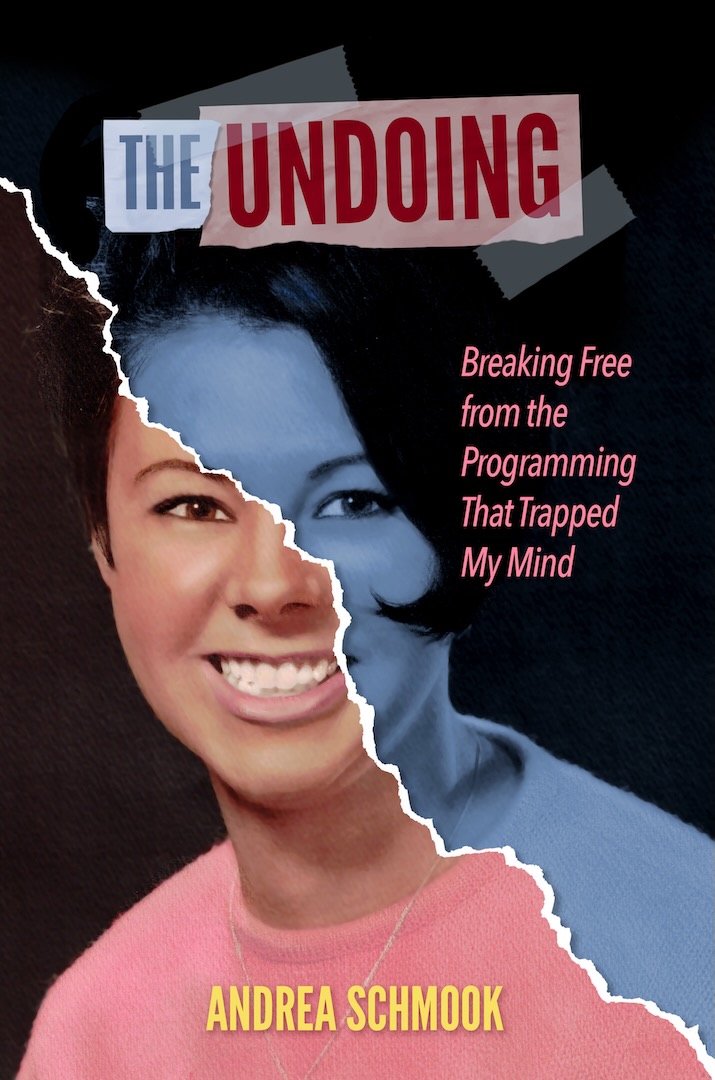

It’s time to take mental health care seriously. Having been suicidal myself, I wrote this book to share how I recovered from mental illness myself, and to inspire others to use recovery and spiritual tools to heal and reclaim their lives.

In 1977, I was diagnosed with acute paranoid schizophrenia at the Alaska Psychiatric Institute in Anchorage, later receiving diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder and manic depression (now bipolar disorder). I used a variety of spiritual practices such as affirmations, meditation, and spiritual principles. Additionally, I had to undo my unhealthy childhood programming in order to re-program myself with the beliefs that would help me get better. This enabled me to heal myself from within, transforming me into a new person—one who was able to recover her life.

These tools were considered radical in the late ‘70s and 1980s, when prospects for recovery were dismal. Before I got well, there was no such thing as recovery, and certainly no acknowledgment of spiritual healing. The only remedy was Thorazine, a psychotropic medication, that was used merely to stabilize and maintain my mental illness—not overcome it. I knew there had to be something more than what was presented as “treatment.”

Mental health professionals have been trained to believe people need medications for life, many with life-threatening side effects. They often promote the idea of chemical imbalances as a cause of mental illness—which is a theory, not proven fact. This negates the impact of real-life traumas and spiritual emergencies. Even in the 1990s, I found no information about spiritual healing regarding mental illness, though I experienced it myself.

By the time I met Patrick Corrigan, Psy.D. (Distinguished Professor of Psychology, Director of the Center for Health, Equity, Education, and Research at Illinois Tech), I was so well-recovered that he initially disputed my diagnosis of severe mental illness. However, as he listened to my story of recovery during my first public speaking engagement, he took note of how the audience embraced my message, eventually concluding that recovery was indeed possible. Later, in 2021, Dr. Corrigan authored The Power of Peer Providers in Mental Health Services, dedicating the book to me, and referring to me as his “first mentor in the power of peers.”

Years later, Catherine G. Lucas’s 2011 book In Case of Spiritual Emergency validated what I had experienced. She stated that mental health professionals don’t understand the relationship between mental distress and spiritual emergency, so they pathologize the entire experience as “illness,” which is damaging to the legions of people caught in the system. Carl Jung similarly concluded that every psychological problem is fundamentally a spiritual problem, stemming from the inability to connect to meaning, purpose, and something larger than oneself.

The spiritual aspects of improving physical and mental health are now backed by scientists like Bruce Lipton, Ph.D., an internationally recognized stem cell biologist whose work bridges science and spirit. The more he researched cells and DNA, Dr. Lipton, who was an atheist, came to believe in God. His research indicates that one’s life can be lengthened or shortened depending on whether cell enzymes are activated or deactivated by real-life experiences. At the forefront of epigenetics, Dr. Lipton shows how behavior and environment affect gene expression. As he says, “We are not victims of our genes, but masters of our fates.”

Dr. Lipton found that our beliefs—not biology—can trigger cellular enzymes to reduce the length of our lives through poor nutrition, trauma, PTSD, and an absence of self-love, and a lack of purpose. Conversely, cells can be activated so that we can live longer through good nutrition, exercise, happiness, gratitude, positive outlook, self-love, service, and purpose. His research suggests that 95% of our life experiences come from subconscious programming (created during our first seven years of life), while only 5% comes from our creative consciousness. We can change this programming through conscious work and effort.

As I read through Dr. Lipton’s research, it suggests to me that spiritual and emotional traumas may contribute to the early death rate of people with severe mental illness, pointing to the potential for recovery through changing how genes express themselves by changing thinking patterns. So many people have suffered these kinds of traumas, but because they’re diagnosed with severe mental illness, they’re treated without hope of getting better.

During the 1990s, the field of neuroscience finally accepted that the brain isn’t in a fixed state but can be rewired through brain plasticity, which involves repeating affirmations and changing thought patterns over time. This confirmed what I experienced using Napoleon Hill’s 1937 book Think and Grow Rich, and his principles of autosuggestion, which were ahead of neuroscience in recognizing that the repetition of affirmations has the power to reprogram minds.

Researcher Courtenay Harding conducted a landmark 32-year longitudinal study of 269 severely mentally ill patients who were discharged from Vermont Psychiatric Center in the mid-1950s. These people received services from community-based rehabilitation programs upon their release, and more than three decades later, she again interviewed the individuals who were still living and found that 34% of them had significantly improved. They were medication-free, employed, and integrated into their communities.

According to Harding, it wasn’t medication that helped these people recover, but participation in community-based rehabilitation programs. In her 2024 book Recovery from Schizophrenia, she emphasizes that rehabilitation services help people find housing, learn community interaction, make friends, and build relationships while reducing symptoms and restoring personhood.

Harding connects this success to neuroplasticity, stating that “We can turn on or off how our genes are read in interaction with our environment.” She purported that many of her colleagues told her she had lost her mind. But despite their skepticism, I am living proof that neuroplasticity works for someone diagnosed with acute paranoid schizophrenia.

Based on the research I present here, and others, I suggest the following important changes: (1) investigate how Dr. Lipton’s findings can help people with mental illness live longer lives based on belief, rather than biology; (2) study neuroplasticity to understand how the brain can change through affirmations, autosuggestion, meditation, and other dynamic tools; and (3) develop systems that distinguish between mental pathology and spiritual emergencies. It’s time to bring the mental health system into the 21st century.

My narrative is written in six parts: Part 1 describes my distress and hospitalization; Part 2 shows how childhood experiences influenced my adult thinking; Part 3 details how my healing journey began; Part 4 captures my spiritual awakening; Part 5 guides readers through my spiritual transformation; and Part 6 identifies the recovery strategies and principles of spiritual healing I applied in order to heal myself from mental illness and reclaim my life.

My book introduces people to recovery through spiritual healing, even if they don’t believe in God. The GROW organization’s program,12-Steps of Recovery and Personal Growth, emerged in 1957 in Australia and was developed from the experiences of people who had been institutionalized. It acknowledges both “horizontal” spirituality (belief in persons) and “vertical” spirituality (belief in God), providing alternatives for those who don’t believe in God. Universal life-giving principles are found in philosophies worldwide, and many who identify as agnostic or atheist acknowledge nature, the cosmos, or even reason itself as a way to provide them with a sense of guidance. There’s no wrong path—the key is knowing which works best for you.

Within the pages of my book are the spiritual tools and recovery strategies I used for overcoming mental illness. I’m convinced that complete healing is possible for everyone because there is more to recovery than endless cycles of prescription drugs, hospitalizations, and talk therapy.

This story reveals my spiritual path—my hero’s journey—demonstrating how I overcame mental illness and everything that came with it, and if I could do it, you can too! I hope my book inspires you to seek your own spiritual path to discover your hero’s journey. I know that it can lead you to healing from within so you can change your life for the better too.